What Is the Coptic Church?

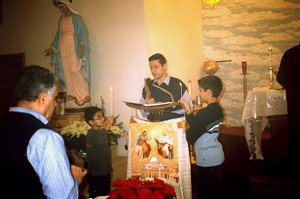

As you may know, San Rocco has welcomed some of our brothers and sisters of the Coptic Orthodox Church, for their weekend Mass at the oratory. They will be welcome again, anytime our facility is available. For some time, there have been two Coptic Orthodox churches in the metropolitan area. A third, St. George parish, is now set up; the church building is in Monee, Illinois, south of us. For some time, Bishop Makarios, the founder, was living at the Augustinian monastery in Olympia Fields, Tolentine, where their liturgy was normally celebrated. Later on, he stayed at St. Irenaeus, a Catholic parish in Park Forest.

What kind of group is this? And what is its relationship to the Catholic Church? Here is a brief explanation. First of all, as you know, St. Rocco is part of the Latin Rite, the Roman Catholic Church. However, there are many Catholics who are not part of the Latin Rite and are certainly not Roman. Many of these Catholic Churches have an Orthodox counterpart, with the same liturgy, law, and tradition. Especially in the Middle East, there are many Orthodox who share the Catholic faith and need only to be in communion with the bishop of Rome to be fully Catholic. In all other respects, their Churches are the full equals of the Western Church.

In the Roman Empire, the most important city was Rome itself, the heart of the dominion. Here, too, tradition says that both St. Peter and St. Paul were martyred. So, the bishop of Rome had immense prestige in the early Church. His legate would preside over an ecumenical council, and his authority was widely respected. For example, Pope Leo I and Pope Gregory I had a worldwide reputation for orthodoxy, for the true faith.

The second most important city in the Empire was Alexandria in Egypt. Like Rome, Alexandria was a center of commerce and trade, especially seafaring trade. As you know from the Epistle to the Romans, the early Roman Church was Greek-speaking. Many of the first converts were slaves, whose native tongue was Greek. Alexandria, like much of the Middle East, was also Greek in language and culture. Since the armies of Alexander the Great came through that region, his culture followed in his wake and became dominant. As with the Norman invasion of England in 1066 and Ireland shortly thereafter, the common people often held on to their native language, in oral form. In England and Ireland, that was English and Gaelic. In Egypt, the native language was Coptic. Up to the present, therefore, the Coptic liturgy is celebrated in both Greek and Coptic, as well as the current dominant language, Arabic. This Church, fully in communion with Rome, never used Latin as a liturgical language.

In the Eastern part of the Roman Empire, Alexandria was without a doubt the most significant metropolis. Its harbor was dominated by a huge statue of Alexander himself. Ships entering the harbor would pass underneath the statue, through the legs. In due time, an earthquake would destroy the statue; it is no longer visible above the water. Especially because of their mutual trade, Rome and Alexandria were closely united, by way of the Mediterranean Sea.

Like the other early councils of the Church, the Council of Chalcedon in 451 was summoned by the Emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire. He wanted to bring about peace in his kingdom. Now, Chalcedon is a suburb of Constantinople, the city that bore the name of Constantine. He made this city his capital in the early fourth century; before that, it was a second-rate city by the name of Byzantium. Only its new, political role made Constantinople important. Twenty years earlier, in 431, the Council of Ephesus had taken place, dominated by St. Cyril of Alexandria and other bishops from Egypt. In fact, St. Cyril started the Council of Ephesus before many Syrian bishops had even arrived.

In one sense, the Council of Chalcedon has been considered as a corrective to Ephesus, restoring needed emphasis on the humanity of Jesus Christ. In another sense, however, the council proved to be needlessly divisive for the Church. More than once, various Bishops of Rome have said that the conflict associated with Chalcedon had a political, cultural, and linguistic foundation, rather than an actual difference in the essentials of the faith.

top

top