Cardinal Cody Is Succeeded by a New Bishop

August 25, 1982 saw the installation of the first Italian American Archbishop of Chicago, Joseph Bernardin, who came here from Cincinnati and, ultimately, from South Carolina. He had a reputation for humility, kindness, and gentility. His coming was much appreciated at St. Rocco and throughout the Archdiocese of Chicago. Especially among the priests, he was warmly welcomed, as an agent of reconcilation and harmony. There was considerable discord among the clergy in the 1970s, and Archbishop Bernardin seemed to be the right man for the job. In many ways, he was. To his death, he enjoyed widespread respect and esteem among the priests. By and large, they gave him their loyalty and cooperation.

After widespread consultation, on January 15, 1987, the Archdiocese of Chicago published criteria for parish planning and evaluation. One criterion was that a parish should not have more than 3000 nor less than 300 registered families. Another criterion was that parishes should be no more than two miles or less than one-half mile apart. These criteria were developed in response to the evident need during the 1980s to consider consolidation or closing, especially within the city of Chicago.

Once grade school enrollment dips below 200 students, for example, it becomes difficult for the school to survive. To the disappointment of many, in the 1980s, Mt. Carmel School had to be closed. From a demographic standpoint, too, Cardinal Bernardin, the Archbishop of Chicago, faced the challenge of keeping parishes open that were no longer viable. In Englewood, a neighborhood in Chicago, priests met monthly but never came to agreement on which parishes should be closed. In Roseland, another neighborhood on the south side, there were seven parishes built to serve immigrants that now stood in an overwhelmingly African-American population. Similarly, in Chicago Heights, the Lithuanian parish of St. Casmir had already been closed. St. Paul's, about half a mile southwest of San Rocco's, was originally Slovak; but the neighorhood was now predominantly Mexican. St. Anne's, originally German, had been entirely English-speaking since World War II; it was just a few blocks south of St. Agnes and so was not necessary. St. Joseph's, originally Polish, was now in a Black neighborhood. Together with St. Rocco, St. Anne's and St. Joseph's were also served by the Franciscans. Now, they informed the Archdiocese of Chicago that they would have to leave these three parishes, because of a shortage of personnel.

About the same time, Cardinal Bernardin had a committee formed to determine what should be done in Chicago Heights. He recommended that they close two of the three Franciscan parishes. With representation from all major parish groups, the committee seemed to have been appropriately set up. Its recommendation was to close all three parishes. Two local pastors, Father Bill Eddy of St. Kieran's and Father Willy O'Connor of St. Paul's, both strongly advocated that San Rocco be closed. Meanwhile, the Fracniscan priests (who would perhaps have supported San Rocco) were no longer present; they had been transferred elsewhere, by their provincial.

As required by canon law, the Archbishop had to consult the priests for their advice, in the presbyteral senate, whose members are elected by the priests. Unanimously, the priests supported the decision of Cardinal Bernardin and his committee. All three parishes, therefore, were closed in August, 1990. The last Mass at San Rocco took place July 1, 1990.

People were asked to go to Mass near the church where they lived, their local parish church. It was pointed out that the vast majority of people at St. Rocco preferred English, as their first language; so, it was said, they no longer needed a church intended for an immigrant population. Those who were of Italian origin were now mostly of the third and fourth generation; because of intermarriage, many people there were of other ethnicity in any case. Priests, too, would be better put to work in the large parishes, where they were needed. St. Michael's in Orland Park, for example, had 5,000 families.

"You Americans Know How to Litigate" (Cardinal Arinze)

Some people cooperated with this decision and joined, for example, St. Kieran's and St. Agnes parishes. But many others were unhappy. Since every Catholic has a right to appeal a bishop's decision, some members of St. Rocco appealed to Rome. They did so without rancor or public protest, fully in accord with their established rights in canon law. In fact, Angelo Ciambrone, at the time the Mayor of Chicago Heights, went to Rome five times; August Anzelmo, corporation counsel, also went more than once. In their appeal, these lawyers argued that St. Rocco should be kept open. It was, after all, debt-free; it also had a good number of practicing Catholics and considerable vitality. In this protracted, legal battle, there were various ups-and-downs, duly reported in the local newspapers.

For example, it was argued that Cardinal Bernardin had not properly consulted the priests of the Archdiocese, in the presbyteral senate. According to canon law, a bishop cannot close a parish without proper consultation. Rome agreed and ordered St. Rocco re-opened. Cardinal Bernardin did so for one day, while he consulted the priests, this time correctly. They voted in his favor, again, on Dec. 11, 1992. The parish was closed immediately thereafter, for the last time. The chancellor of the diocese, who had been originally been directed to see that the closing was done correctly, had not done so. He was now assigned as pastor to a parish in the northern suburbs of Chicago.

At the same time St. Rocco was closed, in 1990, twenty-nine African American parishes were shut down, as well as Good Shepherd in Evanston, which was Polish and Mexican. By closing Good Shepherd and St. Rocco, the Archdiocese could say that they were closing White parishes, as well as Black parishes.

On February 12, 1993, the Archdiocese of Chicago issued a statement explaining its rationale for the closing of St. Rocco parish. Research had indicated that an average of 661 individuals took part in Sunday liturgy at St. Rocco; the number at nearby St. Paul's was somewhat higher. In the immediate area of St. Rocco, one parish was said to be sufficient, especially because of the increase in the local Hispanic population. Therefore, said the statement, St. Rocco's was to remain closed.

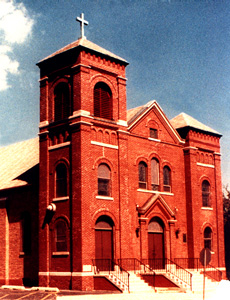

In 1995, bulldozers arrived at 315 East 22nd Street and levelled all the buildings. The church had been vacant for a year; there was water damage and some vandalization. The school, which was relatively new, had also been vandalized. The responsible authorities reckoned that demolition would be less expensive than repair and renovation. All that remained standing was a grotto, to the north, with the stations of the cross.

Hundreds of families were disappointed in the closing of St. Rocco. Many people joined St. Mary's in Park Forest and St. Liborius in Steger, because they did not want to be part of the Archdiocese of Chicago. These two parishes are in the Diocese of Joliet. Other people simply stopped going to Mass. On November 14, 1996, Cardinal Bernardin died.

top

top